UNFINISHED BUSINESS:

FUTURE of the AMERICAN WOMEN’S MOVEMENT

To download a PDF version of this chapter, click here or for large print PDF, here.

This book is dedicated to the 115 million women living in the United States (and sovereign Indian nations) today. We dream of liberty, equality, and justice for future generations—yes. But we also want it for ourselves, in our lifetime. Let’s make it happen.

And, this book is dedicated to Mary Ann Kirby, my great-great grandmother, born around 1850 so of course I never met her. I only just now learned her name. Why, you ask, when this book is about the future and not the past? Because women are still rising, still inspired by our mothers and foremothers. We are still longing for that lost love, that first spirit who valued us, in a world which does not always find us valuable. And—we need their help.

“My task is to figure out what to do right here and now. You can’t just ignore what our grandmothers and great grandmothers did. Nor all those women who never had an opportunity to do anything… I think they’re still working, they’re still alive… I believe they are out there, like muses… I know there are women from history who are orchestrating this still.” – Rev. Joy Bussert, In the Company of Women

“So catch the lilt of the chant to the Grandmother; feel the long centuries of submerged power now breathing through you and wanting to call out its name. Don’t be surprised to find your own lost name chiming in echo.” – Mary Ellen Shaw, introduction to Rites of Ancient Ripening by Meridel LeSueur

What do women want?

“The Unfinished Business Project” is both a book and a video documentary, both being published online as I go. I have been working on this project for a year now. At this writing I have interviewed 24 women on camera, in four states, and beyond that I have been discussing feminist strategy with hundreds of others. Even with this deeply-engaged group, it has been helpful to simplify the long lists of “women’s issues” in order to frame the ultimate goals of our movement. In the past, many of us have used the word “equality” to signify the ultimate goal. However, more and more women tell me that’s not the right word. It doesn’t help, for instance, to assert that men who get pregnant must receive “equal” treatment. Therefore, I am now using “liberty, equality, and justice” to cover all possible bases in the fewest possible words.

More specifically, here is my best quick summary of “women’s dreams”—developed from a one-day retreat with presidents of 18 women’s organizations:

- 51 percent representation at every table

- woman-centered health care, accessible for all

- self-determination/human rights (abortion rights, lesbian rights, and more)

- peace and safety, at home and in our communities

- economic justice (living wage, pay equity, income security)

When you share this easy list, you are already using some of the key strategies outlined in this book:

- offering a short “elevator speech” message which can unite us across all the sometimes-fragmented issues and organizations,

- engaging others in “big picture” discussion (Is something missing? Is there a better way to state any of the dreams? Which issue is most important to you? Can we succeed with any part of this without succeeding at the full agenda?), and

- beginning to envision a positive future beyond all our hard work at damage control.

To me, keeping these goals in mind is much more helpful and important than engaging in one more discussion about the meaning of the word “feminist.” Just sayin’.

About the book: Your thoughts are needed

I have been an active feminist for more than forty years. Please let me know who you are, dear reader, and where you are coming from. My purpose in writing this book is simply to enlist and encourage you in the cause of liberty, equality, and justice for all women—and to offer some strategies for this work.

Early readers, be gentle with me. I have learned a lot from my own feminist work, and much more from the people I have been lucky enough to work with. My goals are ambitious far beyond my abilities, and so your help is needed. I want this book to be as compelling as a cheesy novel and as deep as a Virginia Woolf essay. Please help me offer a toolbox full of ideas and activities which anyone, or any collective, could put to use. Describe a successful action that made a difference, or tell about the lesson you learned from a horrendous flop.

One of the most important strategies for our movement is to connect with people who have not yet been deeply engaged in improving women’s lives—while not letting anyone retire from activism. I keep thinking of the old Girl Scout song, “Make new friends/ but keep the old.” We need to learn from each other, to cross the boundaries of age and class and all other differences. Throughout the book, I claim the right to have some strong opinions based on my long experience—but you must feel able to disagree, expand, and keep the conversation going.

I am publishing each chapter on my blog, UnfinishedBusinessUSA.com, and each video documentary segment on YouTube. At the end of each chapter and each segment, there is a space for comments.

The video series is different from (but with topics related to each chapter of) the book. The video segments can’t cover as much territory, but they have the great advantages of being accessible to people who don’t read books, and showing the beautiful faces of some people engaged in this work. There is a disadvantage to publishing step by step in this way—for example, writing the introduction describing the book before knowing the full content of the book. However, there is a great advantage to periodically revising each chapter to reflect the most helpful suggestions of a growing audience. I believe there are thousands of great thinkers and great doers in this country who have not yet been included in the process of planning for feminist victory. I’m talking to you, dear reader.

To the following call to engagement, and the following good list of “stakeholders,” I add people who do not yet consider themselves part of the women’s movement:

“We must create more radical, intentional, and transformative relationships between all of the stakeholders in the feminist movement—the organizers, students, teachers, academics, activists, philanthropists, and online feminists. When we engage one another in creative, dignifying, and reciprocal ways, we will all be profoundly emboldened.” – Vol 8 #FemFuture: Online Revolution (Barnard Center for Research on Women, 2012) – Courtney Martin & Jessica Valenti.

Radical. Intentional. Transformative. Important words! I feel profoundly emboldened myself. It’s wonderful to have this technology which allows all kinds of feedback, skipping the laborious steps of creating marketing plans and looking for publishers. With luck, I will be able to keep writing successive chapters, and revising and improving previous chapters, in ways that help good things to happen. By the end of 2014, I hope to have published one full iteration of the book and the documentary.

Chapter Summary

Each chapter in this book addresses a key strategy for the future. We need to acknowledge our progress (chapter one) and embrace the possibility of complete victory, with some specifics about what that will look like—let’s say by the year 2030 (chapter two). How about reigniting some of the widespread passionate excitement of the 1970s (chapter three)? In order to make change for everyone, we need to find a balance between supporting organizations and their sometimes complex infrastructures, or supporting individual success (chapter four). We may need to return to something like consciousness-raising, starting with our families, neighbors, and co-workers (chapter five).

In order to achieve liberty, equality, and justice for all, we need to transform all of society. (Did you pause here and think, “Wait, I thought she was writing only about women, not ‘justice for all’ “? I recommend reading Anne Wilson Schaef, Women’s Reality, asserting that only in the “white male culture” does one assume that equality is a zero-sum project.) To transform society, we must continue transforming language and every form of media (chapter six). And what about all those issues women are working on which don’t seem like “women’s issues” – are we losing focus as a movement (chapter seven)?

My experience has been in nonprofit organizations and in government—but other sectors including “the grassroots” are making a dramatic difference also, and women of color are leading the way with new strategies (chapter eight). How can we share power and conquer ageism (chapter nine)? We need to stay engaged with the men who have supported feminist work for decades, and attract new male supporters, while insisting upon our vital self-advocacy (chapter ten). How about the many service groups created to address women’s needs—are they “band aids,” or a vital source of bubbling-up advocacy (chapter eleven)? We are beginning to see new approaches to professionalism, volunteerism, and philanthropy (chapter twelve). Nobody has ever been in charge of the women’s movement—but maybe there could be a group of wise women to promote healthy collective behavior, and what about a sabbatical program (chapter thirteen)? And of course—with your help—there will be brilliant conclusions, with some of my favorite examples of new and promising strategies for the future (chapter fourteen).

Want this outline in list form?

Post-feminist era? Bite your tongue.

I have been amazed, in many conversations, to see the prevalence of the belief in a “post-feminist era.” Few people I talk with actually believe we have eliminated all forms of inequality between women and men, but many seem to suggest we can rest on our laurels. Some think further progress is inevitable. Some say, “We will never be done.” Can I talk you out of those opinions?

Here are more oft-stated assertions and my quick responses, many of which will be addressed in upcoming chapters:

- “You have to admit we have made enormous progress.” (OK, glad to celebrate—but not ready to quit.)

- “Other issues are more important now: environmental justice, voting rights, gun control, immigration reform, racism, homophobia…” (Do you apply the “gender lens” to these issues, and does that change anything?)

- “Things are so much worse for women in other countries.” (My own focus remains the USA—where bad things still happen to millions of women, plenty of them in my neighborhood.)

- “It’s up to the young women now.” (We need a true inter-generational alliance, so don’t walk away, 80-somethings, and keep talking, 20-somethings.)

- “I don’t want to use the word ‘feminist’ because…” (Please, use whatever word you like. I will never stop using that word for myself, but not to panic the scaredy-cats, I sometimes say “the women’s movement.”)

- “Feminists were not inclusive enough, were anti-male, etc…” (Our movement—yours and mine—has never been monolithic. There is plenty of opportunity for you to show the rest of us how to do it the right way.)

- “I can’t stand electoral politics.” (Yes, many times I have held my nose and voted for least worst. If you just can’t go there, please remember that those “inside the system” can really use help from those “outside,” calling attention to the issues.)

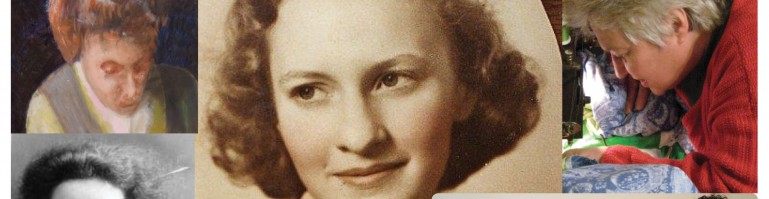

Bonnie Bio (the political is personal)

Before continuing to introduce the book, I want to convince you of my credibility, which requires a bit of biography.

When I graduated from college in 1973, there had been no “women’s studies” classes, but feminism seemed to be in the drinking water. As a 20-something volunteer I helped to found three groups: Women In State Employment, a Ramsey County chapter of the Women’s Political Caucus, and the Minnesota Women’s Consortium. In 1977, I was hired by the Minnesota governor’s office to staff a commission increasing representation of women and minorities on state boards. Then I became assistant director of the Council on the Economic Status of Women in the state legislature.

There, in the 1980s, I became one of the architects of Minnesota’s two still-unique pay equity laws. Moving to the executive branch, I was the first pay equity coordinator, charged with teaching 800 cities, 435 school districts, and 87counties how to implement the new law, and later wrote the administrative rule defining compliance. Exhilarating! Also in those early days and beyond, I was a dues-paying member of many women’s groups, a common practice then.

In the 1990s, Nina and I finished writing In the Company of Women. And I thought I was taking a break from feminist activism when I became executive director of three different Living At Home/ Block Nurse Programs, neighborhood nonprofits serving senior citizens. As it turned out I could not remove the “gender lens”—but I learned a lot about management. Also in that decade, I worked as a management consultant for groups outside Minnesota seeking to achieve pay equity.

In 2003 I became executive director of the Minnesota Women’s Consortium. There I got to know thousands of women connected with hundreds of organizations of all shapes, sizes, colors, issues, and strategies, and learned new perspectives from several dozen college interns. Finally, soon after “semi-retiring” in 2012, I became a crew member for a cable TV show called “It’s A Woman’s World,” where I have begun to learn the technical skills for television, thanks to IAWW producer Mike Rossberg.

I have worked with some national organizations, learning that my experience in Minnesota is both the same and different from women’s experiences in every other state. This book draws much from my Minnesota roots and honors this state’s leadership of the women’s movement. However, the strategies and leaders come from far beyond Minnesota as well. I hope you, dear reader, will further expand the geography by contributing your thoughts.

Great national groups I’ve worked with include: Wider Opportunities for Women, which introduced me to “elder-nomics” in 15 other states; the National Council on Aging, same topic; US Women Connect, with a strong emphasis on leadership by women of color; the Women’s UN Report Network, for whom I travelled to New York for the 2013 meeting of the UN Commission on the Status of Women; and Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders in Philanthropy (AAPIP), especially their National Gender and Equity Campaign which nurtures 30 organizations in many states.

So are you impressed? Truly I am a lucky woman to have been able to do this work, to work shoulder to shoulder with colleagues young and old, with fancy titles and not. The paid jobs I have not listed among my credentials were in many ways the most important. Before moving to the governor’s office, I had been a factory worker (peeling tomatoes), a keypuncher (which we now call data entry), a waitress, a hippie farmer, a teacher aide, a clerical worker. In those jobs I learned a lot about “women’s work,” and I loved most of those jobs. But the persistent injustices of that work fueled not only my passion for pay equity, but my entire feminist worldview. I will share some stories from those days throughout the book.

Yet the story of an activist’s life can never be complete with a job history. What has kept me going?

Bonnie Bio, continued: Motivation

I have always been a woman of privilege. I have always been white, middle class, healthy, able to fit into the mainstream culture well enough, and I had a good education. My husband and two kids are perfect in every way—just ask anybody who knows them—and they sustain me through all kinds of thick and thin. The women’s movement has brought me immeasurable joy and rewards of every kind. And yet the picture is a bit more complicated than you might think.

It’s fashionable to say of almost any issue, “That’s not just a women’s issue—it’s a family issue, a race issue, an issue of…” I can’t help hearing the JUST as a put down for all those things which happen because I am female, because being male is about the only form of privilege I don’t have. I know people say things like that because they want to be inclusive. I recognize that there are multiple reasons for the bad things that happen. I am aware of the injustice faced by people of color, having grown up with Indians, having parents active in the civil rights movement, having a Hispanic child. Sojourner Truth’s speech, “Ain’t I a woman?”—a woman initially left out of the suffragists’ work—rings in my head and I hope our movement never makes that mistake again. And I know “not just a women’s issue” is also a marketing strategy—that is, Representative Schmoe will be more receptive to voting “yes” on a “family” issue than a “women’s” issue. So I must ask the “not just a women’s issue” crowd: what if it WERE just a women’s issue—would it still be worth fixing?

Here are some of the things I have experienced because I am female. I have been sexually harassed in the workplace, by a guy who often ran his fingers up and down my back to see if I was wearing a bra—because he knew I was a “women’s libber.” I have been raped, in fear of my life, and didn’t call it that for a decade because I thought it didn’t count. I have been denied birth control by a prudish doctor, and as a result got pregnant and had an illegal abortion. I have been paid less than men doing far less responsible work, and for many years was “one man away from welfare.” And to this day there are things I don’t do, places I don’t go, and things I do with my heart pounding in fear, because I am a woman. I sure wish I could spare my daughter all those things. But all of those things have been called “just life,” “just the way it is,” for a long, long time. To me, those basic and ongoing injustices, experienced to some degree by 115 million women—that does not need to be “just life.” That’s motivating.

Assumptions and assertions

I make some overriding assertions which will be tested in the course of writing this book and reviewing your feedback.

A key assumption is that we—everyone who cares about liberty, equality and justice for women—need to talk about strategy. The common opinion that “equality will take care of itself” is rarely stated so boldly. But there is plenty of evidence that we are in great danger of moving backwards on the gains we have made, and we have plenty of unfinished business. Would it help if we thought of our movement as if it were a business association, where we could contemplate such things as return on investment, or how to recruit, connect, and retain new leaders and followers across all the barriers, in multiple organizations? What will it take to keep our movement vital?

Another assumption is that we can and must work together across issues and organizations, and that we can share strategies across those lines. Some think this is obvious—but I wonder if we have become so successful at managing our somewhat siloed organizations, that we simply have no time to help each other. For example, can we acknowledge that we are forced to compete with each other in “branding,” visibility, and fundraising for our own organizations, and find ways to reduce the frustration of that competition?

While organizations are often problematic, we need organizational structure and focus—and many organizations working together—to achieve systemic change by the year 2030. The alternative is to nurture individual success for each American woman, all 115 million of us, one at a time. Going to meetings is tiring—we will explore some alternative ways to organize—but think how tired you would be trying to help 115 million women one at a time.

Another assertion has to do with the intertwinement of issues. The term “intersection-ality” is often used to recognize, rightly, that classism, ageism, racism, ableism, homo-phobia, and sexism work together to hurt us all, and there is no fix for one without the other. But in addition, “women’s issues” are all deeply related. Awhile back I asked a leader of a battered women’s group what they were hoping to achieve in an upcoming state legislative session—assuming it would be better funding for shelters, or improving the law on restraining orders. She surprised me by saying, “pay equity.”

Women leaving or trying to cope with violence cannot be liberated without improving their economic status. And so it goes. If we have the right for lesbians to get married but no access to decent health care, how can we call that equality? If we elect more women to the US Senate but they don’t support abortion rights, how will we achieve justice for all?

I assume that our organizations need money. However, I encourage careful thinking about how much money is needed, where it should come from, and recognition that money is rarely our greatest need. Foundation grants are unlikely to ever be the main funding source for our cause. We do have other models for engaging everyone in fundraising and organizing, like the houses of worship in every community.

“[Social change] will require no less a commitment than that which millions of people make every Sunday when they enter a place of worship and drop a check or a $5 bill in the collection plate… Our victories will come through authentically connected membership and organizing. Collectively, we have to build a sense of possibility, grow muscles and courage and joy in the work, and stay strong together in the vision and practice of a transformed world.” –Suzanne Pharr, Political Handywoman blog, “Funding Our Radical Work.”

I assert that our movement needs two new resources: a sabbatical program and an accountability program, both accessible by many individual leaders and many organizations. Having been an activist for so long, I know how tired one can be working long and often lonely, low-paid or unpaid hours week after week and year after year, and how the cynicism can creep in. How can we give each other permission (and financial support, if needed) to take a break (or a study break) and come back renewed after six months or a year? Wouldn’t that be great?

The idea of an accountability program makes us nervous, we the foot soldiers of a movement which is populist and anti-hierarchical. Yet so far as I can tell, the women’s movement has no mechanism for acknowledging or addressing conflict among ourselves. Surely we can find some models, like the wise women of the Iroquois Confederacy who quietly offered their wisdom to the nominal chiefs, to help us speak truth to each other when some feel strongly that important directions and resources are being missed. Surely we can measure success and doing right in ways other than the size of our budgets, or the degree of exposure we receive in the mainstream media.

Some additional assertions will be scattered throughout the following chapters. I believe, for example, that “the feminist leader of the future” will not be the executive director of a nonprofit organization based in Washington, D.C. or New York City—said with great love to some wonderful women who fit that description. Rather, I hope to foment a complex web of many leaders of many additional kinds: in the corporate sector, in the streets, in cultural and faith communities, spread all across the prairie here in the Heartland as well as the trees and mountains and rivers of the Northeast and West and South.

Status of the Project Today

Please check out the two-minute trailer for the TV documentary version of this introduction, or the full 28-minute video introduction, both on YouTube. Each includes a short montage from the 20 women in the early interviews, with short clips hinting at the many creative strategies they are using. Here’s just one example, from the interview with Guadalupe Rodriguez of the Minnesota Indian Women’s Sexual Assault Coalition:

“[We need to] have multiple leaders… in every neighborhood, in every tribe, in every reservation—everywhere. Gaining those leadership skills within. Because everybody has a gift, and that’s how we’re gonna do it, is if we enhance our gifts, and recognize the gifts we bring that we are born with, and bring it to the table to help end it. Because we’re not all gonna be the ones that are good at policy, or good with making law. We’re putting everybody’s gifts in place.”

I am learning as I go along. Two things I am hearing over and over. One is that we need to build healthy relationships across all barriers. I guess I have always known that, but I am slowly learning not to dismiss that strategy as merely “touchy-feely” and taking too long. Smart women are showing me the surprising power, and even the speedy effectiveness, of this strategy. The other lesson I have always known, but need to keep on hearing: that liberty, equality and justice for women—which means liberty, equality, and justice for all—cannot be achieved without a profound transformation in American life. Yes, that’s a tall order, and it won’t happen this week. However, if we don’t begin we will not arrive at that shining day which we are beginning to imagine.

There are rewards along the way. When Nina and I interviewed more than 80 women for In the Company of Women, they were diverse in every way. The one thing they had in common, we learned, was their great delight in connecting deeply with other women. The full video introduction to this book includes, besides the preview of some of the strategies to be discussed, a montage of the first 20 women laughing together in twos and threes, just so you can see for yourself the love, joy, and great fun in this work.

Definitions

Trying to speak to a large and diverse audience, I am trying with this book to avoid scholarly and technical terms. When those terms are needed, as may happen when I get going on pay equity, I will try to explicate as I go along. But the one word which deserves a bit more definition here is “we.” Dare I include one of my favorite jokes, about Tonto and the Lone Ranger?

Lone Ranger: Oh no, we are surrounded by Indians, Tonto! What shall we do?

Tonto: What do you mean “we,” Paleface?

In this book, when I say “we,” I mean you and me, together, and a lot of our friends and family and neighbors and co-workers. I hope that we will succeed, in my lifetime, in helping to make women’s dreams come true.

— Bonnie Peace Watkins, November 2013

Bonnie, Bonnie! Your “Unfinished Biz” blog is astonishing…and terribly, wonderfully important. This should be posted in multiple Big Media settings…and obviously MUST become a book. The video material really adds strength too, but your writing and the YOU in this comes through conveying the passion, urgency and importance of “where to from here”! More more now with coming chapters! A proud, awestruck bro. Angus